By Tsipi Inberg Ben-Haim

Bel Kaufman has her own impressive career as a writer, teacher and lecturer, but she draws the biggest inspiration from her famous grandfather, the great Yiddish writer Shalom Aleichem, still, even at 102, thinking about him every day

Will you offer us a hand? Every gift, regardless of size, fuels our future.

Your critical contribution enables us to maintain our independence from shareholders or wealthy owners, allowing us to keep up reporting without bias. It means we can continue to make Jewish Business News available to everyone.

You can support us for as little as $1 via PayPal at [email protected].

Thank you.

“Today, at the age of 102, I step into the future, ” Bel Kaufman tells me clearly. She hears my unspoken question, and adds, as if it were obvious, “I’m working on my website and my two eBooks were published in October.” And with chin up nobly, quiet and proud, she continues: “I was very busy. All of September was dedicated to finishing translations and carefully going through each book, which will not only be published in English.”

Among the books of Bel Kaufman, granddaughter of the great Yiddish writer, Shalom Aleichem, are two novels. The best known is called “Up The Down Staircase, ” which tells of a teacher struggling with the difficult laws of the new school where she teaches, including the principal’s repeated demands …. Kaufman herself was a teacher, and despite her deeply ingrained love for teaching, she gave up her teaching career for writing, mainly because of the success of this novel, which was published in 1965 to great acclaim. To the same extent, and perhaps to a greater extent, she enjoyed giving speeches, lectures and public readings. She is very natural on stage and always starts with a joke. Bell’s second book is called “Love etc, ” and her most recent work includes a collection of essays called, “This and That, ” and a collection of short stories called, “The Tigress.”

Two years ago, Players Club gave her a lifetime membership for her hundredth birthday. “It was the most wonderful party of my life, ” she said, and added with a smile, “But I told them that at my age I deserve a refund for a lifetime membership.”

The talent for public reading and writing flows through the veins of the Bel Kaufman’s remarkable family. “They all wrote, my mother and father, even though he studied medicine and worked as a doctor.” The father was urging her to finish her undergraduate degree in 1934 at Hunter College, which, at the time, was a women’s college in the United States. Last year, at the same college, she taught a course on Jewish humor. “Not only did we tell jokes in this course. We were engrossed in trying to understand how it is that so many comedians are Jewish and why their jokes are almost always directed toward themselves.”

She completed her master’s degree in literature at Columbia University and continued teaching high school literature….. I look at the woman sitting across from me: a beautiful, well-groomed woman, her fair hair in a sixties style, makeup, silk scarf tied gently around her neck, and a white jacket hugging her shoulders. I bend down, smiling, and ask, “Are you still dancing?” She looks at me with her thoughtful eyes and places her hand on mine… Leaning forward, she looks at me and asks: “Are you still breathing?”

I joined Bel one year ago at her dances. Without them, she told me, life is not life. It intrigued me to see a woman her age dancing in a dance hall. It was not fancy but very elegant. Ten professional dancers stood in front of twenty women eager to dance with the best. The music starts to flow and the dancers lead ten women to the sounds of tango, waltz and Fasdovlh, in sensitively sweeping dances. The women smile. Ten minutes later, it’s time to change and the women waiting for their turn stand up. Bell, wearing a bright pantsuit and heels, rises from her chair with deliberate slowness, as if a Prince had just held out his hand and invited her to dance. The professional dancers all know her and her age. They are aware that they must move to her beat. “The only problem, ” she tells me later, “At my age, I sometimes lose my balance.”

He called me Belaschke

Bel Kaufman was born in 1911 in Berlin, where her father studied medicine. When he graduated, the family returned to live in Odessa, where he worked as a family physician. Bel’s mother, the daughter of writer Shalom Aleichem, wrote as well but not professionally. She especially liked to write a family journal and Bel learned a lot about the family history.

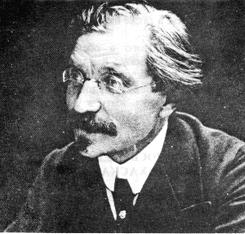

“Papa Shalom Aleichem was very significant in my life as a child, ” she says. “We called him Papa. He was young in spirit and very entertaining. It was hard for me to think about him or call him Grandpa.” Shalom Aleichem, the pen name of Shalom Rabinovich, lived in New York in his later years and would send letters to his little granddaughter, who still lived in Odessa.

“I looked forward to the letters that came for me to Odessa. He called me Belaschke. I keep the letters today. One of the letters he wrote:” Do not eat a lot of candy. And grow up quickly so you can write me letters, too. “I learned to write as I grew older, “says Bel, ” but not fast enough. In May of 1916, she received a telegram from America: “Papa is very sick.” She never saw him again. “I remember it was very difficult for my parents to tell me the bad news.”

Bel talks about Russia before the revolution with nostalgia and love, despite the pain that accompanied her childhood. She remembers the Odessa city as one of poets, musicians, Jewish intellectuals. “It is important to note that Shalom Aleichem always looked like a great intellectual, not someone who came from the shtetl! He liked to wear velvet suits and always look groomed as if on his way to a special event. He also used to correspond with the great Russian writers, Leo Tolstoy and Maxim Gorky, ” Bel emphasizes the Russian accent.

“Shalom Aleichem’s fans, who love to read and love him deeply. This is a special kind of love, unlike readers’ love for any other writers.” It’s just hard to explain why, she says. “He entered into their souls, has become an integral part of the lives of readers, and has grown and developed a special bond between the reader and the writer.” In his will he asked to be remembered once a year in the way that his readers loved him: through his writing. Therefore, once a year, an event is organized so that fans can gather stories and read his books. Indeed, for the last 96 years, on the third Sunday in May, Bel’s family organizes this special memorial event for reading the stories of Sholom Aleichem. Last May, dozens of people, most of them over the age of 50, shared reading scriptures, including the author’s will, which is an interesting and exciting document itself. The document is in both Yiddish and English and shows his sensitivity to his family and reflects that he did not want to burden them by carrying the responsibility of preserving his literary legacy after his death.

A sad, funny story

One of the people invited to read his stories was Jerry Adler, who had performed in the television series “The Sopranos” and “The Good Wife.” “I love the stories of Shalom Aleichem, ” says Adler, “so this is the third year that I happily volunteered to read to this group that especially loves Shalom Aleichem. Most of them are at an advanced age, it is true, but I am one. I’m 80 years old as well.” Each year, Bel’s son sends him a collection of stories of Shalom Aleichem and Adler chooses the one that sits closest to his heart. “It’s not easy to choose, because every story is wonderful, full of humor and sadness.”

Bel and her brothers, sons, daughters and grandchildren participate in the annual tradition in order to preserve the flame. Additional guests come from near and far to listen to these stories. A mature couple, in their 70s, told me in a whisper: “We have come from Maryland every year for 20 years. This is our special journey as an annual trip to New York.” And, in more than a whisper, the woman adds, “Do not forget to go down after the stories, to drink tea and eat Rogallach”. They are part of a special club once a year that feels like an island of Shalom Aleichem: the shtetl with Tevye the Milkman and the smells and tastes that accompany it.

“At first he wrote only in Yiddish, the language of the kitchen, ” says Bel. “He liked to build his characters, loved the humor and laughter of the people he wrote about, described with his additional charm. He would say a doctor gave them a special prescription: laugh until you cry – a full and healthy laughter to help overcome the troubles of those who have lost everything and yet continue to laugh.”

At the age of three, she noted in an interview with me, she helped Shalom Aleichem to write. “When we were walking together side by side on the street and I’m a child of three holding his big hand, he would say, ‘the stronger you hold my hand, the better I’ll write.” He wrote more than 400 stories. Despite the fact that he was full of humor and made everyone laugh, “Shalom Aleichem was a very sad man, ” says his granddaughter. “He lived a hard life, it’s like chasing something that was never achieved……… there were illnesses that plagued him every day.”

Shalom Aleichem died at age 57. More than 10, 000 people attended his funeral in New York. People still call him that special world of Jewish storytelling. Many will remember him mainly as the author of the story “Tevye the Milkman, ” which served as the inspiration for the successful musical “Fiddler on the Roof.” “Papachka, taught me to speak in rhyme, ” says his granddaughter. “He taught me to make people laugh. One of the pleasures of my life is to make people laugh.”

Bel’s own life, as an adult, has not always been happy, particularly when it comes to her marriage. She tells of an unhappy marriage, where she stayed because of the circumstances and because social norms of the time dictated that it is better to stay in a marriage and rot than to get a divorce. But at the age of 50, she took courage and decided to get up and go, with very few in number with and without a penny in her pocket. A few years later, she published her first book, a great success. This was followed by her second book, “Love Etc.” “If you must decide which of my books you want to read, you should start with Love Etc., ” she says.

Inspiration from Grandpa

Kaufman began her literary career with the decision to send her short stories to “Esquire” magazine, but because the magazine did not publish stories written by women in the ‘40s, she decided to send the stories under the name “Bel.” “It was in this way that I could be a man, ” she thought, and she ventured forward. The stories were accepted for publication. “I am the first woman whose stories has been published in ‘Esquire, ’” she says. “Because of the historical importance, I decided to keep the name Bel.”

Odessa Memories

The third book is “My Odessa, ” which nostalgically recalls her memories of the Ukrainian city located on the shores of the Black Sea. At the end of the 19th century, the city became a Jewish center – spiritual and main stage of modern Hebrew literature. Bel remembers the Odessa before the Communist revolution of 1917. She writes about the broad avenues of the dead and icy streets. She remembers walking with her baby brother in a carriage on a street near their home. Two women came to her, took her brother out of the carriage, gave it to her wrapped in a blanket and took off with the wagon. “We have babies, ” they told her. She ran home in tears and told her parents about what happened. From this point on, the family was looking for a way out because they were part of the Jewish bourgeois class as destitute communities were rising around them.

Shalom Aleichem -Greatest Yiddish writer of the Lower East Side.

“We lived in a private house, ” she writes, “with servants and valuables and of course we were considered the Bourgeois, the enemies of the revolutionaries………

Even during those terrible days, they tried to continue living a normal life, and on Friday evenings they were invited to the homes of friends, writers, and artists. One of them was Chaim Nachman Bialik — in one of his songs, he even wrote about her playing with her dolls. They sat around the table and talked with excited energy of poetry and literature, and the price of wood to heat the house …

One day a week, a Hebrew teacher came to their home to give her lessons. “I remember only one sentence and I never used it: I want a horse. What I liked most to do as a child was to recite the poems of Pushkin, who also once lived in Odessa. I also loved to listen to songs in Russian and Yiddish on the gramophone.”

Grandpa Shalom Aleichem was in America, on the Lower East Side of Manhattan, when he died a year before the revolution, in 1916. During his years in New York, he would also send letters with packs that included chocolate. Bel remembers that the chocolates were important treasures, and they ate it only occasionally so as not to finish them quickly. “We were acting like little mice, rodents eating a tiny bit each day. The taste was wonderful, ” she writes, “It was like eating chocolate in Switzerland. It was only when we got to America we discovered it was cooking chocolate.”

The political situation was worsening and bourgeois hatred grew so much that some members of her family were arrested under false pretenses. Since Shalom Aleichem’s stories continued to be published during this time, Bel’s mother decided to take advantage of this connection to leave the country. The Minister of Culture allowed them to leave the country to visit America, a visit from which the family never returned. In 1968, Bel Kaufman came to visit Odessa, 45 years after she left. She was invited by the Union of Soviet Writers but reported that the visit was not very good. “I came home like a stranger, ” she wrote.

In her notes from her second visit Kaufman writes:

“In 1998 I came to Russia as a VIP to reveal the plaque honoring my grandfather, Shalom Aleichem. On 28 Kantnih Street, a placard written in Yiddish and Ukrainian noted: ‘In this house, in 1893-1891, worked the great Jewish writer Shalom Aleichem (Naumovic Rabinowitz, 1916-1859).’ Crowds of people came to hear and talk to me. There were microphones, televisions, and endless questions. They poured over me the love they had for Shalom Aleichem. ”

No complaints

Bel now lives in Manhattan with her husband Sidney Gluck, who is 6 years younger. “He likes older women, ” says Bell chuckling. She has a daughter, Tia, a 68-year-old psychologist, and a son, Jonathan Goldstein, a 70-year-old computer science professor. “Today I think I can say that I’m the only living person who can say I lived when Shalom Aleichem was alive. His biggest fear was that I’ll not remember him, but I remember him every day…He influenced my Childhood and will continue to influence me until my last day.”

Eliane Reinhold, Bell’s friend for 30 years, tells me about the trip to Washington University they took together in May, where Bel Kaufman gave a lecture on her writing to the students. “Bel stood for two hours on high heels and after the lecture, we went to the city center where she opened the festival of Shalom Aleichem, ” says Eliane, herself a musician and producer who runs the Foundation, “Holocaust Requiem.” “Bel is really great, ” she says. “Spirited, optimistic, I never heard her complain. Not even a small KVETCH.”